Date created: April 2009

Author: Lynda Wallace-Hulecki, B.Sc., M.Ed., Senior Consultant, SEM WORKS

For further information, contact the author at

SEM WORKS

407 Pebble Ridge Court

Greensboro, NC 27455

Web: www.semworks.net

E-mail: lwallace-hulecki@semworks.net

Abstract

The demographic profile of students involved in post-secondary education in Canada is changing as the overall demographic profile of this country is changing. This SEM WORKS white paper presents a high level overview of the demographic trends impacting post-secondary enrolment in Canada, the issues associated with educating an increasingly multicultural and diverse student population, and the application of theory-based principles in creating the conditions for their educational success. The strategies presented in this paper have been drawn from the literature as examples of effective SEM practices associated with enhancing student diversity and success.

I. Canada as a Multicultural and Diverse Nation

Canada is often described as a multicultural nation, reflecting the vast diversity of the cultural heritages and racial groups of the Canadian population. Over the coming decade, it is projected that the demographic profile of Canada’s population will become even more diverse and multicultural in nature. These demographic shifts will increasingly transform the student population served by Canada’s higher education system, and in turn will place greater pressure on colleges and universities to respond to the needs of students that are vastly different from those served in past decades. Among the most disadvantaged groups in Canada are Aboriginal people (North American Indian, Métis, and Inuit)―a population segment that is expected to grow at twice the rate of the total population of Canada to 2017, as well as new immigrants―a population segment that is likely the fastest growing source of labour force supply into the future, and that is projected to constitute almost half the population of Toronto and 44% of the population of Vancouver by 2017. Therefore, higher education professionals must understand the demographic trends impacting enrolment, the issues associated with educating an increasingly multicultural and diverse student population, and the application of theory-based principles in creating the conditions for their educational success

A. New Immigrants

In Canada, birth rates have been below replacement levels since the early 1970s, and the Baby Boomers (born between 1946 and 1966) who represent the largest segment of Canada’s population are fast approaching retirement. Therefore, Canada has become increasingly dependent on immigration as a source of labour force supply. Between 2001 and 2006, immigration was responsible for two-thirds of Canada’s population growth (Statistics Canada, 2007a). By 2017, it is projected that about 20% of Canada’s population could be visible minorities (i.e., anywhere from 6.3 million to 8.5 million people), with the vast majority (95%) residing in major urban centres. Close to half of the foreign-born population are projected to be South Asian or Chinese (Statistics Canada, 2007b).

Taken from Statistics Canada, 2007

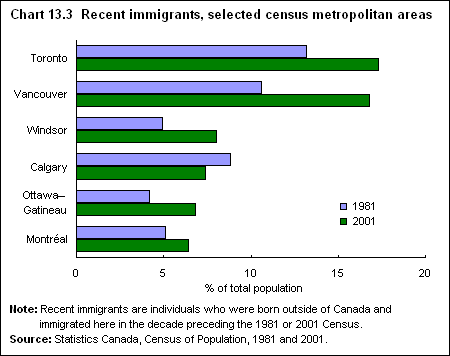

According to the 2006 Census profile of Canada’s foreign-born population, Toronto, Montréal, and Vancouver attracted almost 70% of recent immigrants. The majority of the foreign-born population emanated from Asia, including the Middle East (58%), followed by Europe (16%), and then Central and South America and the Caribbean (11%). The immigrants who arrived in Canada since 2001 were overrepresented in the younger age brackets compared with the Canadian-born population.

While there is controversy regarding whether the demand for immigrants will remain as high during times of economic downturn, the issues affecting post-secondary access and participation remain critical to the long-term health of the Canadian economy, as immigrants’ language skills, cultural insights, market knowledge, and business contacts are critical to Canada’s success within what is an increasingly diverse and global economy (Kitagawa, 2008). Recent research on new immigrants highlights some important facts for post-secondary enrolment planning:

-

Immigrants often settle close to family and friends who are more likely of similar ethnic background, which may contribute to a strong sense of belonging to their ethnic group (Statistics Canada, 2007b).

-

Children of immigrants tend to be more educated than those with Canadian-born parents ―Over 65% of children whose parents come from China and India completed university, compared to 28% of youth whose parents are Canadian-born. Nearly one-third of youth of Caribbean, Portuguese, and Dutch immigrant parents finished university (Statistics Canada, 2002).

-

Many first-generation Canadians come from families whose parents do not have a post-secondary education (PSE), and often encounter greater challenges to post-secondary participation than their peers with educated parents. While immigrant parents’ financial investments in their children’s educational futures are complex and vary by background and PSE purpose, they tend to share with non-immigrants a set of parenting beliefs and practices that lead them to allocate limited family resources to their children’s educational futures (Anisef, P., Walters, D., & Sweet, R, 2008).

-

Almost two-thirds of new immigrant workers in 2006 had a post-secondary qualification. However, many faced difficulties having their credentials and work experience recognized within Canada―a considerable waste of talent (Kitagawa, K., Krywulak, T., & Watt, D., 2008).

-

In terms of PSE participation, some researchers have argued that overall participation patterns for most ethnicities are in line with their population numbers, albeit with observable differences within some ethnicities [Junor and Usher, 2004, in the Educational Policy Institute (EPI), 2008].

-

Research on visible minorities in the United States present some interesting parallels between the issues facing Latino people who are underrepresented in the American PSE system, and Canada’s Aboriginal and particular visible minorities. The common issues identified in the research include: “higher dropout rates, lack of preparedness for postsecondary study, importance of peer encouragement, the culture of ‘possibility’ needed to support students’ dreams for PSE, financial supports, and informational deficiencies” (see Baumann, et. al., 2007, in EPI 2008, p.6).

B. Aboriginal People

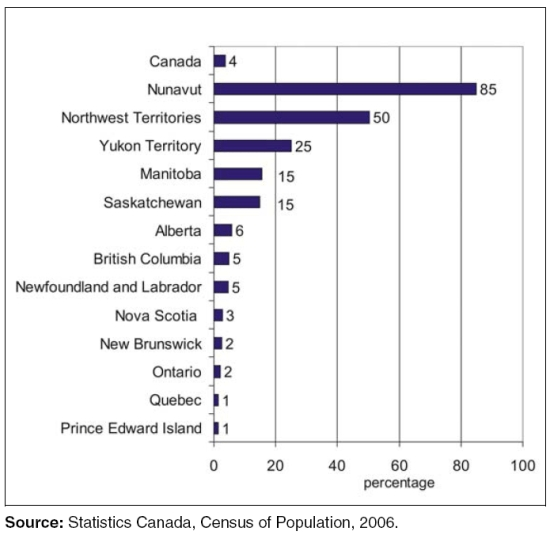

Aboriginal people in Canada encompass hundreds of communities with diverse cultures, languages, as well as governance structures and treaty agreements. According to the 2006 Census, there were more than one million self-identified Aboriginal peoples in Canada, representing 3.8 percent of the total Canadian population (CCL, 2008b). This population increased by 6 times the rate of non-Aboriginal people over the period 1996–2006, and about half of the Aboriginal population was under the age of 24. It is projected that the Aboriginal population will grow at twice the rate of the total population in Canada to 4.1 percent by 2017 (AUCC, 2007).

Eight in ten Aboriginal people live in Ontario and the western provinces, with Winnipeg, Edmonton, and Vancouver being the three largest urban centres, respectively (Statistics Canada, 2007c).

Only 6% of working age Aboriginal people has a university degree, as compared to 20% for the Canadian population (AUCC, 2007, p. 20).

Aboriginal people require the skills and credentials acquired at university to achieve self-government, self-determination, and healthy communities (Mendelson and Usher, 2007). While post-secondary enrolment and attainment rates have grown substantially over recent decades among this segment of the population, particularly within the non-university sector, equity of access remains a significant challenge. Recent research on Aboriginal people highlights some important facts for post-secondary enrolment planning:

-

Over 40% of Aboriginal young adults (10–24-year-olds) have not completed high school compared to only 16 percent in the total population, and the on reserve rate of failure to complete high school is even higher—averaging 58 percent across Canada, and as high as 70 percent in Manitoba and 60 percent in Quebec, Saskatchewan, and Alberta (Mendelson, 2006).

-

Aboriginal people are more likely to complete high school as young adults when compared to the rest of the population. Therefore, PSE readiness can occur at a later age (CCL, 2008a).

-

Aboriginal PSE participants tend to be older, married, and have children―partly reflecting their greater likelihood of delaying entry into PSE after high school (Canada Millennium Scholarship Foundation, 2006; Holmes, 2005; O’Donnell and Tait, 2003; Looker, 2002; in EPI, 2008).

-

As is the case with other Canadian youth, the decisions of Aboriginal youth regarding the pursuit of PSE are affected by factors such as family income, parental education, parental expectations for their children’s PSE, high-school performance, proximity to a PSE institution, and financial planning. However, other factors more unique to this population include: historical distrust of educational institutions (a vestige of residential schools and institutionalized practices of assimilation), lack of preparation at the secondary level (a consequence of high dropout rates, limited funding for on-reserve and remote schools, and less likelihood of completing subjects required for university entrance), poverty of Aboriginal communities, feelings of social discrimination within society, and difficult and expensive relocation, which separates the individual from family and community ties and obligations (CCL, 2008a).

-

Finances and distance are among the primary barriers for Aboriginal high school graduates in pursuing a PSE (Canadian Millennial Scholarship Foundation, 2008b).

-

In terms of post-secondary attainment levels, in 2006 an estimated 44% of Aboriginal people aged 25 to 64 had completed a post-secondary certificate, diploma, or degree, as compared to 61% of the non-Aboriginal population. Aboriginal people were on an equal footing with their non-Aboriginal counterparts for both college (19% vs. 20%) and trade (14% vs. 12%) attainment. The wide gap in university degree attainment between the Aboriginal (8%) and non-Aboriginal populations (23%) accounts for most of the difference in overall PSE attainment. Eliminating the education gap between Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal learners has become a key education priority of The Council of Ministers of Education in Canada (CMEC), as stated in their April 2008 framework for education in Canada titled, Learn Canada 2020 (CMEC, 2008).

Addressing issues of access, persistence, and completion for at-risk populations requires a deep understanding of the systemic issues underlying family income and PSE financial support for students, inequity of opportunities during secondary school, admissions issues, and lack of information about the benefits of post-secondary education (OECD Tertiary Education for the Knowledge Society, 2008, in CCL, 2008a). New research has been recently introduced to examine these issues more seriously. For example, in 2005, The LE,NON_ ET Project was initiated as a joint study between the Canadian Millennium Scholarship Foundation (CMSF) and the University of Victoria. The overall aim of this initiative was to develop strategies that promote Aboriginal student retention and success. Another applied research project, Foundations for Success, was initiated between CMSF and three Ontario community colleges―Seneca College in Toronto, Mohawk College in Hamilton, and Confederation College in Thunder Bay―in conjunction with R.A. Malatest & Associates Ltd. The intent of this study was to investigate ways of improving the retention rates of Ontario college students who were deemed at-risk of not completing their program. Preliminary results from both studies available at the time of writing this paper indicated positive results to date (see University of Victoria, 2008, and Malatest, 2009, In Baldwin & Parkin, 2009).

C. First-Generation Post-Secondary Participants

Recognizing that many underrepresented population segments are first-generation PS participants, numerous studies by Terrenzini, Watson, and others have been conducted particularly within the American context to understand issues associated with access and persistence with groups who often are less academically prepared and have greater social demands than more traditional student segments. These researchers tend to agree that while many institutions have introduced marketing strategies to attract greater numbers of under-represented groups, few have been successful in creating the conditions for these students to connect with their campuses and successfully complete their studies (Jenkins, 2009). Some of the greatest challenges noted for first-generation post-secondary learners were: lack of academic preparedness (particularly in reading, math, and computer science) and college survival skills. Other contributing factors of significance included: the role and influence of parents/families in the decision process, cultural identity, and family and financial obligations.

II. Strategies for Enhancing Student Diversity and Success

The demographic profile of students involved in post-secondary education in Canada is changing as the overall demographic profile of this country is changing. According to the 2005 Canadian Undergraduate Survey Consortium, 16% of undergraduate students who were surveyed self-identified as visible minorities (AUCC, 2007, in Guo & Jamal, 2008). With nearly 20% of Canada’s total population being foreign born—the second highest in the world after Australia (2006 Census), coupled with 7% of full-time undergraduate student enrolment and almost 20% of full-time graduate student enrolment coming from international jurisdictions, student enrolment in higher education is being transformed. Within this context, the management of student enrolment has become a matter of dynamic complexity.

While many institutions have adopted more sophisticated strategies to target and recruit increasing numbers of diverse students, there is growing recognition of the importance of strategies to enhance student persistence, progression, and success. Much of the literature regarding student retention and why students leave PSE focus on the social and academic integration of students with the institution―a concept based largely upon the early works of Vincent Tinto and his Student Integration Model (1975). Tinto’s theory posited that students’ ability to conform to or integrate into the social and intellectual membership of the institution is pivotal to their ability to persevere through graduation. Beyond Tinto’s works, there is an abundance of literature that substantiates the following core principles of effective strategic enrolment management (SEM) practices:

-

A student learning-centred service orientation,

-

Cultivation of engaging student-institutional relationships,

-

Proactive assessment of student needs and referral to appropriate institutional resources,

-

Academic and social integration of students within and outside the classroom with a focus on the development of the whole person (intellectual, emotional, physical, and spiritual).

The strategies that follow have been drawn from the literature as examples of effective SEM practices associated with enhancing student diversity and success. It should be noted that while there is a growing body of literature on the barriers associated with diverse student populations, there is relatively little research available on the effectiveness of the SEM strategies introduced to address them. Therefore, the strategies set forth in this paper should not be considered as a cookie-cutter solution, but rather as illustrative of the types of initiatives that are being implemented by institutions that have made a strategic commitment to enhancing student diversity. The success of such initiatives depends upon the specific dynamics and culture of each institution.

The strategies are organized into three clusters of activities, which collectively comprise the core elements of The Student Success Continuum (see diagram).

Adapted from Bontrager’s Student Success Continuum (2004)

These include:

-

Strategies for Building an Institutional “Student Learning-Centred” Service Orientation—where students’ needs and student learning are at the centre of all institutional operations and decision-making

-

Strategies for Increasing Access and Participation—including initiatives associated with attracting (marketing), recruiting, admitting, and supporting targeted student segments in transitioning into and through their educational pursuits.

-

Strategies for Improving Student Persistence, Performance, and Completion

-

Strategies Associated with Academic Programs—including the nature of programs offered, curriculum design, instructional delivery, and class-based experiences

-

Strategies Associated with Co-curricular Support—those activities that occur outside the classroom, but are intended to augment the classroom experience (e.g., experiential learning, academic advising)

-

Strategies Associated with Student Learning Support—programs and services that strengthen students’ academic preparedness, ongoing performance, and development throughout their educational life cycle

-

Strategies Associated with Wellness and Campus Life—activities associated with the personal and social aspects of the student experience

-

A primary underlying antecedent to success across all of these types of strategies, and an area of particular challenge for many institutions, is the need to develop both a “student learning-centred service orientation” and “cultural competence” across the organization that are in keeping with the demographic shifts in student populations.

1. Strategies for Building an Institutional “Student Learning-Centred” Service Orientation

Research suggests that campus culture, specifically the influence of leadership styles of campus leaders, is inextricably tied to the success of retention programs for achieving diversity (López-Mulnix and Mulnix, 2006). Institutions with a holistic, socially responsible, collaborative, and caring ethos tend to characterize those that are more likely to encourage diversity and excellence in multicultural policies and procedures. Examples of strategies suggested in the literature as being fundamental to the development of such an inclusive culture include:

-

Faculty/Staff Hiring Policies—Institutional hiring policies that promote diversity among all categories of employees have proven successful in diversifying the employee base, which in turn can serve as “pillars of inspiration” to those aspiring to achieve similar goals (López-Mulnix and Mulnix, 2006, p. 18).

-

Governance Structures—The symbolic presence of governing board structures and senate policies specific to diverse groups, such as Aboriginal students, often signals institutional commitment to their success. Many institutions have successfully introduced Aboriginal governance bodies, such as Simon Fraser University, the University of British Columbia, and Nipissing University, to name a few (Mendelson and Usher, 2007).

-

Faculty/Staff Orientation and Development Sessions—The use of orientation and development sessions for all faculty/staff can create cultural sensitivity and better equip campus constituents in understanding issues associated with multi-ethnic identity, as well as with other factors impacting student motivation and engagement, such as familial support requirements, especially among first-generation PS participants (Evans, Forney, & Guido-DiBrito, 1998, p. 87).

-

Commitment to Diversity in University Mission—The inclusion of a clear commitment to diversity within an institution’s mission has been noted in the literature as an antecedent to the success of multicultural initiatives in general (López-Mulnix and Mulnix, 2006; Copper, 2008).

2. Strategies for Increasing Access and Participation

Student enrolment services focus on attracting academically qualified students, providing them with timely information, orientation, and transitioning support services before and following admission, as well as throughout the undergraduate experience. Research suggests that social and cultural origin can influence both the way decisions regarding post-secondary participation are made and the type of institution of choice. While the extent to which parents’ educational background influences student participation in PSE remains a matter requiring more in-depth research, there is general agreement throughout the literature that parents and families play a significant role in the decision process (Auclair, Bélanger, Doray, Gallien, Groleau, Mason, & Mercier, 2008). Studies also show that student performance in secondary school, “cultural” factors in the student’s background, and to a lesser extent, student financial support are all important considerations in enhancing access and participation in PSE among underrepresented student segments (EPI, 2008). Select strategies identified in the literature that may mitigate some of the associated barriers to student access and participation include:

-

Recruitment/Marketing Outreach—Diverse recruitment strategies are needed to reach Aboriginal people and newcomers to Canada. Given that word-of-mouth is among the primary means by which people learn of educational opportunities, it is important to spread the word among families, coworkers, and employees by engaging alumni and local employers in promoting PS opportunities at community events (e.g., art or country fairs, chamber of commerce events), in communicating with human resource personnel (particularly in local businesses offering tuition reimbursement), and in participating at campus-based events (e.g., career fairs) (Copper, 2008).

-

Customized Information—Customized marketing, recruitment, and admission information that is specific to the needs of diverse student segments is key to enhancing access. Providing appropriate information when and where it is needed is crucial for potential students’ decision-making, both in terms of whether to participate in postsecondary study and what to study (EPI, 2008). Information cited in the literature as being of particular importance included: available programs, standards for admission, housing, visa, medical, actual financial costs, return on investment, work study, orientation, social connections, as well as future career prospects. The ability to demystify the processes associated with admissions and student financial aid assessment was noted as been equally important.

-

Programs to Enhance Academic Preparation and Transition—Research shows that students with secondary grades below 70% were less likely to go on to PSE in Canada than students who reported grades of 70% and above (Barr-Telford, et. al., 2003, in EPI, 2008, p.12). Examples of strategies for enhancing the academic preparedness and transitioning of students to PSE include: early intervention programs that incorporate both an academic preparatory component and educational planning component; summer bridge programs that incorporate both assessment and remediation; extended orientation programs that emphasize academic and cocurricular integration; supplemental mentoring programs; proactive academic advising and career development programs offered prior to admission; and peer support networks involving older students in assisting younger students in navigating post-secondary life. In a case study conducted by López-Mulnix and Mulnix (2006) on Models of Excellence in Multicultural Colleges and Universities, the following schools were identified as offering innovative pre-enrolment practices aimed at enhancing student retention among diverse student segments:

-

Iowa State University, Ames―The College of Education Minority Recruitment and Retention program offered through the Office of Minority Student Affairs―This retention program involved three specific initiatives: a First-year Learning Team aimed at enhancing the academic foundation of students through peer mentoring, tutoring, career exploration, and social activities; a Faculty Research Internship program that assigns minority students as research assistants with faculty members; and an annual minority student retreat with workshops on leadership and self-awareness.

-

Texas A & M University, College Station―The ExCel (Excellence uniting Culture, Education, and Leadership) extended orientation program offered through the Department of Multicultural Services―This year-long student success program targeted incoming students and their parents. The program involved biweekly seminars on pertinent topics, and a peer support program where upper-class students serve as team leaders. The ExCel program was augmented by several other student success programs for minority students, demonstrating the campus-wide commitment to improving student life and learning.

-

University of St. Thomas, St. Paul, Minnesota―Research Excellence in Academics and Leadership projects offered through the Department of Multicultural Student Services―This project involved a scholarship-based 6-week academic and cocurricular orientation program that was offered to a select group of committed minority students prior to matriculation. The program encompassed academic and social life experiences, as well as a mentoring program that was provided by faculty and staff.

-

Georgia College & State University, Milledgeville―The Minority Advisement Program (mentorship-based) and outreach programs offered through the Office of Multicultural Affairs―These programs augmented the normal institutional academic advising services with resources such as a multicultural library, a community outreach program to educate the campus community, and an advocacy program.

With respect to Aboriginal students, Mendelson and Usher (2007) highlight a number of pre-enrolment outreach programs targeted at acquainting first generation Aborginal PS participants, such as the University of Calgary’s native ambassador program, the University of Regina’s native mentorship program, Lakehead University’s outreach science programs for First Nations youth, the University of Winnipeg’s eco-kids programs, as well as summer camp programs offered by the University of Alberta, the University of British Columbia, and others. In addition, the outcomes of the research on The LE,NON_ ET Project at the University of Victoria and the Foundations for Success project with three Ontario community colleges may provide new insights on the effectiveness of a number of innovative strategies (see www.millenniumscholarships.ca/en/research/ppFFS.asp):

-

University of Victoria―The LE,NON_ ET Project―This project focused on the effectiveness of five initiatives: 1. providing financial aid to qualifying students; 2. providing an opportunity to engage in research with the university’s faculty or staff; 3. placement with an Aboriginal community in a co-op arrangement; 4. mentoring students; and 5. raising awareness among staff and faculty and coordinating/ improving support services.

-

Seneca College, Mohawk College, and Confederation College―Foundations for Success―This project was designed to gauge whether case manager-mediated support services increased the probability of completing a college program, and whether financial incentives in combination with case manager-mediated support services increased the probability of completing a college program more than case manager-mediated services alone.

-

Ease of Credit Transfer and Recognition for Prior Learning―Many new immigrants in particular have previously earned PS credit. The marketing of transfer credit and prior learning assessment options as a means to reduce the time and financial investment in earning a degree may be attractive to many prospective students (Copper, 2008). This information should be integrated into recruitment/marketing materials and made available through easy-to-navigate promotional materials and the institution’s Web site.

-

Use of Rituals in Building a Sense of Community―Understanding the beliefs and values of diverse student segments and reflecting respect for these during key events such as on move-in day or through the campus tour program, can create a sense of belonging (Coomes, 2004, p.25).

-

Parent Orientation Sessions―Sessions focused on first-generation students’ families, augmented by written communication sent to families and personalized outreach are strategies that have been identified as creating a sense of belonging (López-Mulnix and Mulnix, 2006; EPI, 2008 ).

-

Flexible Financing Options―While there is considerable controversy regarding the degree to which cost and cash flow constraints affect access and persistence, the literature suggests that financial barriers relating to tuition fees are likely to have a greater impact on people from lower income families than they do on people from wealthier backgrounds, and therefore it has been argued that solutions should be targeted rather than universally applied (EPI, 2008, p.12–16). More specifically, the literature suggests that consideration should be given to assigning priority to the allocation of needs-based aid as well as merit-based scholarships to targeted groups (Jenkins, 2009; Copper, 2008). In addition, non-traditional students in general have variable life circumstances that impact their ability to pay for education under traditional fee payment schedules. Therefore, flexible payment options should be considered, as well as programs such as on-campus work-study, cooperative education, and/or service learning experiences that help to mitigate the cost of education while linking the work experiences to academic learning outcomes (Copper, 2008). These resources should be promoted to prospective students and their families during the recruitment and admissions processes.

-

Flexible Leave Policies and Procedures―Recognizing the diverse profile of non-traditional students, offering flexible options for interrupting studies without penalty can be advantageous, particularly if accompanied by clear advising and check-back communications (Copper, 2008).

3. Strategies for Improving Student Persistence, Performance, and Completion

a. Strategies Associated with Academic Programs

The current curriculum and teaching practices in higher education are often characterized by Eurocentric perspectives, standards, and values, and do not reflect the knowledge and experiences of a culturally diverse student population. Utilizing demographic statistics in curriculum decisions, policy reviews, and program development can build on the strengths of multi-ethnic cultures to enrich the curriculum and enhance participation in PSE. By way of illustration, recent research conducted by the Canadian Council of Learning on Aboriginal learners and the sciences has documented the impact of the cultural mismatch between Western and Aboriginal science (CCL, 2007b) and its impact on student participation in related programs. Examples of strategies identified in the literature that may mitigate some of these issues include:

-

Collaborative Partnerships with High Schools―New models of collaboration, such as the Early College High Schools for Native Youth at Antioch University in Washington state, has shown early signs of success (CCL, 2007b). This program is designed for high school students to earn up to two years worth of post-secondary credits while completing their high school diplomas, and therefore bypasses remediation options that are the common pathways applied by most institutions. The program is modeled on high standards and culturally relevant curricula―a model that may have broader application for Aboriginal learners (and possibly other underrepresented populations) beyond science education. Another model of collaboration is that offered by the Louis Riel Institute, where a host of adult learning programs and initiatives are provided, such as in-school cultural programs, stay-in-school programs, and family and adult literacy, mentoring and role model programs (Mendelson and Usher, 2007).

-

Summer Transition and First-Year Experience Programs―Programs to strengthen the intellectual competence and survival skills of students prior to entry have reportedly had proven success, particularly for select underrepresented student segments. These programs have proven most successful when combined with systematic and comprehensive assessment, remediation, learning, tutoring, and proactive advising services (Watson, Terrell, and Wright, 2002, in Jenkins, 2009). In addition, mentoring programs and first-year experience programs can help to bridge academic and social aspects of student life and provide experiences that build confidence and a sense of community. These forms of programs require collaboration between faculty and student affairs professionals. Whether or not such programs should be mandatory is a matter of some debate and depends in large measure on the philosophy and values of the institution regarding student learning and development.

-

Inclusive Teaching and Assessment―To achieve more inclusiveness in class-based experiences, Guo and Jamal (2008) suggest that teaching practices should be reviewed in relation to the following key questions:

-

What are the cultural and linguistic backgrounds of students?

-

What challenges have been encountered in responding to these differences?

-

Are current teaching methods and strategies working, and do they respect and encourage diversity?

-

How relevant is the course content to students, and does it incorporate the perspectives and world views of minority groups?

-

-

Learning Communities―It has been argued that the who and the what of learning are inextricably linked with the how of learning (Lardner, 2003). There are a variety of pedagogical strategies that are rooted in research on teaching, learning, and diversity that promote learning environments, which create opportunities to connect learning and life, or to put new learning into meaningful contexts. The use of learning communities when designed and introduced in partnership between educators and student affairs professionals has been noted as a powerful tool.

-

Provision of Language and Cultural Studies―Many institutions have developed and offer multinational language and cultural studies, which signals institutional commitment to diversity.

-

Flexible Course Scheduling and Delivery―New immigrants, Aboriginal people, and socio-economically disadvantaged populations in general are often older than traditional-aged students at the time they attend PS institutions. Many have life, family, and work circumstances that create barriers to attending courses during prime time. Therefore, evening, weekend, and online courses can offer greater flexibility and enhanced access to educational opportunities. It is important to note this strategy is likely more successful when flexible scheduling is applied across full programs (versus select courses), and when coupled with proactive and timely academic program planning advice to students upfront so that they develop clear expectations and a timely program completion plan (Copper, 2008).

-

Collaborative Programs and Research with Communities―Programs that are designed to meet the economic development needs of specific regions and communities are becoming of growing importance, particularly with First Nations communities (Mendelson and Usher, 2007).

b. Strategies for the Cocurricular Experience

Cocurricular support refers to those activities that occur outside of the classroom but that augment the class-based experience. These often take the form of experiential education activities (e.g., work-study, cooperative education, service learning, practica), as well as various forms of mentorship and advising support services. The literature suggests that these activities are most powerful when the activities are learning outcomes-based and integrated with the academic curriculum; and when mentorship and advising support is more structured, particularly for students who are at-risk. Many newcomers to Canada gain employment in jobs that are not commensurate with their international work experience, credentials, or skills and competencies, and career advancement is often one of the main reasons for PS participation. Strategies identified in the literature that may address some of the needs of underrepresented student segments include:

-

Industry-based Experiential Education for New Immigrants―Examples of strategies that may serve the new immigrant population include: developing industry-specific language training programs in partnership with industry employers; workshops for employers on the benefits of a diverse workforce; workforce bridging programs for newcomers at the level for which they have been trained while addressing other language and settlement needs; prior learning and experience recognition for foreign credentials and work experience; and workforce transition and preparation programs that inform newcomers about workforce expectations (Kitagawa, 2008). In addition, promoting and providing employment assistance programs specific to the needs of new immigrant students who are in-course or graduating can facilitate employment transition. These programs might include resume writing, interviewing and job search skill development, career counseling, job fairs and internship opportunities with local businesses (Copper, 2008).

-

Advising Services―Building on Tinto’s research on the importance of social and academic integration to student retention, planning for regular personalized points of contact with advisors, peers, and alumni is pivotal to building a sense of community and confidence for non-traditional students in general throughout their educational careers (Copper, 2008). Effective advising practices are integrated throughout the student experience, beginning at the pre-enrolment stage. Among non-traditional student segments in particular, intentional advising practices should include various forms of advising with peers, staff, and faculty from identity-specific backgrounds. In the case of Aboriginal people, multiple connections with Aboriginal counselors, elders, graduates, and peers helps to provide needed living-learning social support systems (Mendelson and Usher, 2007).

c. Strategies for Student Learning Support

The effective integration of student learning support programs and services have been noted throughout this paper as critical to strengthening students’ academic preparedness, ongoing performance, and transitioning from the first point of contact at the pre-enrolment stage throughout their educational experience. Collaborative efforts between faculty and student affairs professionals are required to effectively deliver integrated services at the various stages in the students’ educational life cycle. For example:

-

At the pre-enrolment stage―Collaborative efforts are required to develop summer bridge programs, parents and family programs, extended orientation, tutoring and advising, career exploration and counseling, and learning assessment and skill development programs.

-

During the first-year or entry-year experience―Collaborative efforts are required to develop such support programs as: entry-year experience courses, peer and/or faculty-staff mentoring, proactive academic advising for at-risk students, facilitated group study, supplemental instruction, career activities, living-learning communities, learning support programs for students on academic probation, to name a few.

-

At the upper-year levels― Collaborative efforts are required to develop such support programs as: seminars on majors leading to career, graduate school exploration, internships, undergraduate research, and study abroad opportunities.

The literature reinforced the importance of connecting students who have need for enhanced support systems with programs designed to address their specific needs (Copper, 2008; Lardner, 2003; Keeling, 2006; Evans, et. al., 1998; López-Mulnix and Mulnix, 2006).

d. Strategies for Student Wellness and Campus Life

Wellness and Campus Life services refer to the personal and social aspects of student life that support the well-being of the whole person (intellectual, emotional, spiritual, and physical). Student success is codependent on the sense of “fit” between the individual learner and the institution as a community. Services that traditionally fall within this area of the student experience include: residential life programs, athletics and recreation, personal counseling, child care, chaplaincy, health and food services, social activities, among others. The creation of a vibrant living and learning community has been well documented as a key component in student success programs. Strategies that specifically support multicultural groups include:

-

Affordable and Inclusive Housing―Opportunities for living-learning activities and communities that include students with children as well as with extended families is of increasing importance for Aboriginal people and new immigrants (Mendelson and Usher, 2007). There is considerable controversy about what happens when students are exposed to people of different backgrounds from their own. Recent longitudinal research at UCLA suggested that there was a generally positive impact on racial attitudes from students who were exposed to other races and ethnicities in living arrangements. The most striking positive impacts involved those living with black and Latino roommates; but the one exception involved those living with Asian students as roommates (Jaschik, 2008). The study suggested that institutions should temper the emphasis on minority organizations and activities, as these may tend to “polarize” rather than create an inclusive community.

-

Service Partnerships with the Academic Community―There is abundant literature on strategies to promote social and academic integration. For example, athletics activities have been demonstrated to be effective learning venues in the teaching of leadership and teamwork; service learning activities that are learning outcomes-based can create a sense of community while contributing to class-based learning; campus dining services can work in partnership with student cultural societies and faculty with expertise in multicultural studies to provide intercultural food festivals. It has been argued that these programs often do not require more resources, but rather make better use of existing resources (Keeling, 2006, p.13).

III. Conclusion

The Canadian system of higher education is among the most accessible (along with the United States) in the world. However, it is far from equitable in terms of access to educational opportunity for many segments of society, most notably Aboriginal people and new immigrants. While much has been accomplished in recent decades in addressing barriers to access and participation, there remain substantial gaps in PS achievement among these segments of society who are vital to the economic and social well-being of our nation into the future.

The literature is replete with references to the need for PS institutions to reconsider traditional models of operation, and to create more integrated and coordinated approaches for addressing the needs of diverse populations. Innovative strategies are required to create learning organizations that are student learning-centred, inclusive, and sensitive to the unique needs of multicultural learners; to increase access to and participation in PSE; to develop and deliver academic programs that are aligned with the changing environmental context and diversity of student needs; and to enhance student persistence, progression, and completion through new models of learning support that engage student affairs professionals as partners with educators in the learning process. While there is a growing body of literature on the barriers to access, participation, and retention for diverse populations, it has been noted in the literature that there is relatively little research available on the effectiveness of the strategies that have been introduced by institutions to address them.

References and Resources

Association of Universities and Colleges of Canada. Trends in higher education: enrolment (Volume 1). 2007. Ottawa, Ontario. Retrieved October 1, 2008, @ www.aucc.ca/_pdf/english/publications/trends_2007_vol1_e.pdf

About Canada Publication Series, Centre for Canadian Studies at Mount Allison University in cooperation with Canadian Heritage Canadian Studies Programme. www.mta.ca/faculty/arts/canadian_studies/english/archived/theaboutcanadapublication.html

Anisef, P., Walters, D., & Sweet, R,. Immigrant Parents’ Investments in Their Children’s Post-Secondary Education. 2008. Number 38. Canadian Millennium Scholarship Foundation. Montreal. Retrieved March 17, 2009, @ www.millenniumscholarships.ca/en/research/ResearchSeries.asp

Auclair, R., Bélanger, R., Doray, P., Gallien, M., Groleau, A., Mason, L., & Mercier, P. 2008. Transitions —Research Paper 2 —First-Generation Students: A Promising Concept? Canadian Millennium Scholarship Foundation. Retrieved March 17, 2009, @ URL MISSING

Baldwin, N., & Parkin, A. Persistence in Post-Secondary Education in Canada: The Latest Research. 2009. Research Note #8. Canadian Millennium Scholarship Foundation. Montreal. Retrieved March 17, 2009, @ www.millenniumscholarships.ca/~semworks/httpdocs/images/Publications/090212_Persistence_EN.pdf

Canadian Council on Learning. Post-secondary education in Canada: Strategies for success. 2007a. Retrieved February 14, 2009, @ www.ccl-cca.ca/CCL/Reports/PostSecondaryEducation/PSEHome/?Language=EN

Canadian Council on Learning. The cultural divide in science education for Aboriginal learners. 2007b. Retrieved March 10, 2009, @ www.ccl-cca.ca/CCL/Reports/LessonsInLearning/LinL20070116_Ab_sci_edu.htm

Canadian Council on Learning. Post-secondary education in Canada: Meeting our needs? 2008a. Retrieved March 10, 2009, @ www.ccl-cca.ca/CCL/Reports/PostSecondaryEducation/PSEHome/?Language=EN

Canadian Council on Learning. State of learning in Canada. 2008b. Retrieved October 1, 2008, @ www.ccl-cca.ca/CCL/Reports/StateofLearning/

Canadian Millennium Scholarship Foundation. 2008a. LE,NON_ ET Pilot Project: [Interim Evaluation Report]. Montreal. Retrieved March 17, 2009, @ www.millenniumscholarships.ca/~semworks/httpdocs/images/Publications/081125_LENONET_EIR_final.pdf

Canadian Millennium Scholarship Foundation. 2008b. In Pursuit of Post-Secondary Education. Whether and When to Go on. Montreal. Retrieved March 17, 2009, @ www.millenniumscholarships.ca/en/research/ResearchSeries.asp

Coomes, M. (2004). Understanding the historical and cultural influences that shape generations. New Directions for Student Services. Serving the Millennial Generation. 206, 17-31. Wiley Periodicals, Inc.

Copper, B. (2008). Changing demographics: why non-traditional students should matter to enrollment managers and what they can do to attract them. November 2008. SEM Source, American Association of Collegiate Registrars and Admissions Officers. Retrieved March 29, 2009, @ http://consulting.aacrao.org/2009/02/27/changing-demographics-why-nontraditional-students-should-matter-to-enrollment-managers-and-what-they-can-do-to-attract-them/

Council of Ministers of Education, Canada. Learn Canada 2020. 2008. Available from http://www.cmec.ca/Publications/Pages/default.aspx?cat=0&page=3&sort=Publication.PublicationDate&dir=desc

Donovan, J. and Johnson, L. (2004). Exploring the Experiences of First-Generation, Multiethnic Undergraduate College Students. Vol. 14. Available @ www.sahe.colostate.edu/Journal_articles/Journal_2004_2005.vol14/Exploring_Experiences.pdf

Educational Policy Institute. (2008). Access, Persistence, and Barriers in Postsecondary Education: A Literature Review and Outline of Future Research. Toronto: Higher Education Quality Council of Ontario. Retrieved March 10, 2008, @ www.heqco.ca/SiteCollectionDocuments/Access%20Persistence%20and%20Barriers%20in%20Postsecondary%20Education.pdf

Evans, N., Forney, D. & Guido-DiBrito, F. (1998). Student Development in College: Theory, Research and Practice. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Frame, K.(2006). No higher priority: Aboriginal post-secondary education in Canada. Retrieved March 10,2009, @ http://cmte.parl.gc.ca/Content/HOC/committee/391/aano/reports/rp2683969/aanorp02/08-rep-e.htm

Guo, S. & Jamal, Z. (2008). Diversity in a World of Learning; Emerging Issues and Challenges in Cultural Diversity. Society for Teaching and Learning in Higher Education. 49. 1–3. Retrieved October 14, 2008, and taken from www.mcmaster.ca/stlhe/documents/STLHE%20Number%2049.pdf

Jaschik, S. (2008). A new look at the impact of diversity. Inside Higher Education. December 19, 2008. Retrieved October 14, 2008, and taken from www.insidehighered.com/news/2008/12/19/diversity

Jenkins, A. (2009). Serving millennial first-generation students of color. Recruitment & Retention. February 2009. Resources for Higher Education. Magna Publications.

Kitagawa, K. 2008. A Brave New World for Canada’s Colleges and Institutes. College Canada. 13(1), 11–19. Association of Canadian Community Colleges.

Kitagawa, K., Krywulak,T., & Watt, D. 2008. Renewing Immigration: Towards a Convergence and Consolidation of Canada's Immigration Policies. Conference Board of Canada. Retrieved March 17, 2009, @ www.canadavisa.com/canadian-immigration-recommendations-conference-board-canada-081103.html

Lambert, M., Zeman, K., Allen, M., & Bussière, P. (2004). Who pursues postsecondary education, who leaves and why: Results from the Youth in Transition Survey. Catalogue no. 81-595-MIE-No. 026. Ottawa: Statistics Canada Culture, Tourism and the Centre for Education Statistics Division.

Lardner, E. 2003. Approaching Diversity through Learning Communities. Washington Center for Improving the Quality of Undergraduate Education. No. 2. Winter 2003. Retrieved February 4, 2009, @ http://learningcommons.evergreen.edu/docs/Winter2003-Number2.doc

Keeling, R. (ed. 2006). Learning Reconsidered 2: A Practical Guide to Implementing a Campus-Wide Focus on the Student Experience. Available at www.naspa.org

Mendelson, M. 2006. Aboriginal Peoples and Postsecondary Education in Canada. Caledon Institute of Social Policy. Retrieved March 10, 2009, @ www.caledoninst.org/Publications/PDF/595ENG%2Epdf

Medelson, M. and Usher, A. The Aboriginal University Education Roundtable. Caledon Institute of Social Policy and Education Policy Institute. University of Winnipeg. May 2007. Retrieved March 10, 2009, @ www.uwinnipeg.ca/index/cms-filesystem-action?file=pdfs/conferences/2007/aboriginal-rt-spring-report.pdf

López-Mulnix, E., and Mulnix, M. (2006). Models of Excellence in Multicultural Colleges and Universities. Journal of Hispanic Higher Education. 5(1), 4–21. Sage Publications.

Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development. Tertiary Education for the Knowledge Society: OECD Thematic Review of Tertiary Education: Synthesis Report. 2008. Paris. Retrieved March 18, 2009, @ www.oecd.org/dataoecd/20/4/40345176.pdf

R. A. Malatest and Associates, Ltd. (2004). Aboriginal Peoples and Postsecondary Education: What Educators Have Learned. Montreal: Canada Millennium Scholarship Foundation. Retrieved March 10, 2009, @ www.millenniumscholarships.ca/~semworks/httpdocs/images/Publications/aboriginal_en.pdf

Statistics Canada. University completion rates among children of immigrants. 2002. Retrieved October 14, 2008, @ www.statcan.ca/Daily/English/080922/d080922b.htm

Statistics Canada. (2007a). Immigration in Canada: A portrait of the foreign-born population, 2006. Ottawa: Statistics Canada. Retrieved March 13, 2009, @ www12.statcan.ca/english/census06/analysis/immcit/index.cfm

Statistics Canada. (2007b). Ethnic Diversity and Immigration. Ottawa: Statistics Canada. Retrieved March 13, 2009, @ www41.statcan.gc.ca/2007/30000/ceb30000_000-eng.htm

Statistics Canada. (2007c). Aboriginal Peoples in Canada in 2006: Inuit, Métis and First Nations, 2006 Census. Retrieved March 13, 2009, @ www12.statcan.ca/english/census06/analysis/aboriginal/surpass.cfm#02

Swail, W.S. (2002, July/August). Higher Education and the New Demographics: Questions for Policy. Change, 15–23. Retrieved February 4, 2009, @ www.educationalpolicy.org/pdf/higherED_demographics02.pdf

Swail, W.S., Redd, K.E., & Perna, L.W. (2003). Retaining Minority Students in Higher Education: A Framework for Success. ASHE-ERIC Higher Education Report: 30(2). Retrieved February 4, 2009, @ http://educationalpolicy.org/pdf/Swail_Retention_Book.pdf

Tinto, V. (1992). Leaving College: Rethinking the Causes and Cures of Student Attrition (2nd ed.). Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

United Nations Association in Canada. 2008. Creating a Sense of Belonging: Report on the Survey Results of Canadians’ Attitudes on Racism, Discrimination and Multiculturalism issues in Canada (February 2008). http://unac.org/ready/en/research/SB-surveyreport-FINAL.pdf

About the Author: Lynda Wallace-Hulecki is a seasoned professional with over thirty years experience in higher education. Lynda has provided leadership in strategic enrollment management at both a research-intensive university and a four-year comprehensive college in Canada. Lynda also served for twenty-three years at the college as director of institutional analysis and planning. As a graduate student at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln, Lynda has focused her graduate research on the evolving field of SEM, and the application of learned concepts on leadership, change management, and strategic planning to the advancement of SEM as a professional field of practice. In November 2007, Lynda joined SEM WORKS as a Consultant.